In the first episode of her YouTube series, Yekaterina Petrovna Zamolodchikova discusses the nature of truth and memory. There are, she says, three version of events: the objective truth of What Happened, the remembered truth of the people who experienced What Happened, and the reported truth. Events occur, and then they pass through filters—filters of memory, of identity, of conversation. People lie, and people misremember. People manipulate the truth for purposes of entertainment and personal gain and cruelty.

Over time, the Objective Truth can come to feel completely inaccessible, lost to all the people who’ve divided it into pieces and swallowed those pieces and digested them into stories and gossip and history. The prospect of trying to unravel it all to find out what really happened can feel like an insurmountable obstacle.

But author Mallory O’Meara is an unstoppable force.

Milicent Patrick created the Creature from the 1954 film Creature from the Black Lagoon. This statement should not be controversial. Creature from the Black Lagoon is a classic monster movie, famous and successful, and the titular Creature is a marvel of design, living in the strange intersection between practical effects, costuming, and makeup. Someone created that Creature, and the identity of that creator should be an objective fact, the answer to a Jeopardy question, a Horror trivia-night staple—but a coordinated campaign, waged by an insecure and ego-driven man, all but erased Milicent’s name from the history of the Creature. That man received the credit for the design and creation of the Creature; Milicent faded into obscurity, and from there, she faded further, until all that was left of her legacy was a handful of memories scattered among those who knew her.

Until now.

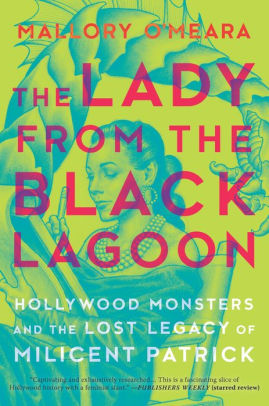

The Lady from the Black Lagoon is Milicent Patrick’s biography, written by Mallory O’Meara. It’s also a memoir of O’Meara’s own experiences in the film industry, and it’s also an indictment of the way women are treated, in the film industry and throughout the world. The Lady from the Black Lagoon is honest, vulnerable, and searingly compassionate. Make no mistake: O’Meara’s open subjectivity is not only a strength—it’s downright revolutionary.

From the very start of The Lady from the Black Lagoon, O’Meara makes no secret of her lifelong admiration for Milicent Patrick. The book chronicles O’Meara’s search for the Objective Truth of Milicent’s life story—a truth that is highly disputed and incredibly difficult to track down. O’Meara is transparent about how the search for the truth about Milicent feels. She shares disappointment with the reader, and admiration. She shares uncertainty and trepidation and hope. And throughout The Lady from the Black Lagoon, she does something I’ve never seen in a biography of a woman: she openly and explicitly respects and believes her subject.

Milicent Patrick created the Creature from Creature; this is an objective, provable truth. But she got attention for it, and that attention made the wrong man feel insecure, and so he buried her and blacklisted her. As O’Meara documents, people today believe the story that man spun, in spite of ample evidence that he is a liar (and an asshole. Like, a huge asshole. Sorry…no, I’m not: he’s terrible).

Buy the Book

The Lady From the Black Lagoon: Hollywood Monsters and the Lost Legacy of Milicent Patrick

O’Meara doesn’t believe the story that man spun. She believes Milicent, and because of that, she digs into Milicent’s life and story. She searches out documentation, and she talks to people who have answers, and she reports her findings. In some places, she finds that Milicent was dishonest; with sympathy and with empathy, she explores the reasons behind those lies. In other places, she finds that Milicent was truthful, and she defends that truth with concrete evidence. O’Meara also exposes the liminal truths of Milicent’s life, the truths that exist in the space between fact and memory and legend — for example, Milicent’s claim to have been the first female animator at Disney, which isn’t quite true and isn’t quite a lie, either. In her exploration of this and of so many other areas of Milicent’s life, O’Meara treats her subject as human, respecting the way that memory and personal myth can blur the facts of one’s history.

Because O’Meara approached Milicent’s story from a perspective of good faith, The Lady from the Black Lagoon is staggeringly kind. I have never seen a woman’s life examined with such kindness, which (it bears saying) is not and has never been the opposite of truth. O’Meara holds space for Milicent’s brilliance and for her failures, presenting her strengths alongside her weaknesses. This biography is factual and emotional, honest in every way that honesty can apply to a life.

Difficult as it can be to define what is true, there’s one fact of which I have no doubt: The Lady from the Black Lagoon is a marvel.

Author’s note: I know Mallory O’Meara personally. Normally, I would say that makes me too subjective to write about her book. But then I read her book, and I realized that writing with care doesn’t mean writing with dishonesty. I could write a whole other piece on how that entire mindset is broken and objective analysis doesn’t exist, but that’s for another time.

The Lady from the Black Lagoon is available from Hanover Square Press.

Hugo, Nebula, and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Their work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. They are a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to their work here. They tweet @gaileyfrey. Their American Hippo novella series—River of Teeth and Taste of Marrow—is available from Tor.com, and their upcoming novel Magic For Liars publishes June 2019.

Hugo, Nebula, and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Their work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. They are a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to their work here. They tweet @gaileyfrey. Their American Hippo novella series—River of Teeth and Taste of Marrow—is available from Tor.com, and their upcoming novel Magic For Liars publishes June 2019.